Old postcards are like time capsules preserving glimpses of the past. We see things long lost, but also timeless continuity. They provide important records of the way things were and different social practices and experiences. The maker produces images for a specific audience with its own attitudes and values. This webpage explores the early Canada Lake postcards. To flesh out our understanding of the images, it will draw heavily on the historical record provided by Barbara McMartin’s Caroga, An Adirondack Town Recalls it Past.

As a webpage, it is open to continual revision. This account is mostly based on postcards that were available online. The conclusions are therefore based on partial evidence. It is hoped that others will share their collections to supplement and expand this account.

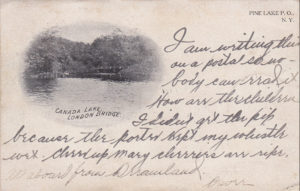

Before 1898, only the Post Office could print “postals” or postcards. The earliest known postcards from the Lake date after 1898, but they continued the practice of acquiring them at the local Post Office.  The one illustrated here has a vignette of London Bridge. The message was required to be on the side of the picture while the reverse is dedicated to the address only.

The one illustrated here has a vignette of London Bridge. The message was required to be on the side of the picture while the reverse is dedicated to the address only.

The card identifies the Post Office that distributed it, in this case Pine Lake P.O., N.Y. which was the Post Office for Caroga located at the “Five Corners”. The 1903 USGS map records the l0cation of the Pine Lake Post Office.

In 1898, Congress passed an act that allowed private printing companies to produce “Private Mailing Cards” which could be sent for a penny. This act was revised in 1901 when the Postmaster-General issued an order that allowed the “Post Card” instead of the longer “Private Mailing Card.” These cards allowed for an image on one side while the other side was dedicated to the address only. These changes led to an explosion in the market with a number of printers becoming involved. The period between 1901 and 1911 has been characterized as the “Golden Age of Postcards.”

Some of the earliest postcards of Canada Lake were produced by the New York City based Rotograph Co. that was in business from 1904-1911. Like most postcards at this early period, the Rotograph cards were printed in Germany. United States printers could not compete with German ones. The card entitled “Road to Canada Lake, N.Y. and Canada Lake Stage” copyrighted 1905 is typical of Rotograph cards. The font used in the caption in the wide bottom borders is characteristic of Rotograph. Any message would be placed at the bottom with the reverse being left for the address.

Rotograph produced different versions of the same image. The caption for the “Road to Canada Lake” card is prefaced with the tag “A 4323.” The letter prefix refers to the type of card. “A” refers to a black and white printed collotype. The “H” prefix identifies a handcolored collotype. The number identifies the card as a part of a series of Canada Lake cards including postcards of the Canada Lake Hotel and Auskerada Hotel.

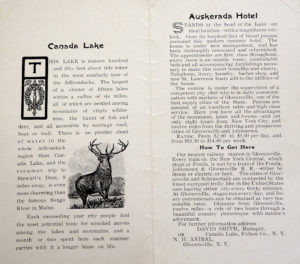

Seeing this as a series suggests a narrative with the Canada Lake Stage climbing the mountain to one of the resort hotels. A brochure for the Auskerada presents the following description of the stage: “At Gloversville, stages run every day, and livery conveniences can be obtained at very reasonable rates. Distance from Gloversville, twelve miles -a ride of two hours through a beautiful country picturesque with nature’s adornment.”

In his memoir All Unplanned, Paul Bransom gives us the following account of the stage up from Johnstown to Fulton’s Hotel in 1908:

After dinner in the old hotel, we were conveyed to the lake in a horse-drawn stage. I recall that the horses would have to rest once in a while on the hills for, although the distance is only about eighteen miles, Canada Lake is almost a thousand feet higher than Johnstown and there are some real climbs. I remember a spring where the horses rested and drank. In fact, we all drank some of that clear, cold water. The spring is still there and running strongly. Today, lots of people to continue to come and get water. It’s a good idea. That water is cold and delicious [All Unplanned, p. 97].

This was the era of the grand hotel in the Adirondacks. Luxury hotels attracted well-to-do vacationers away from the urban world to a backwoods retreat. A brochure for the Auskerada emphasizes this: “Each succeeding year city people find the most potential tonic for wrecked nerves among the lakes and mountains, and a month or two spent here each summer carries with it a longer lease on life. ”

At the same time the brochure calls attention to the luxury and convenience of the hotel: “The appointments are first class throughout; every room is an outside room; comfortable beds and all accompanying furnishings necessary to make this resort homelike and cheery. Telephone, livery, laundry, barber shop, and new St. Lawrence boats add to the utilities of the house…. Patrons are assured of an excellent table and high class service.” The inclusion of telephone poles in both the “Road to Canada Lake” and “Canada Lake Hotel” cards suggests the importance of “modern” communication.

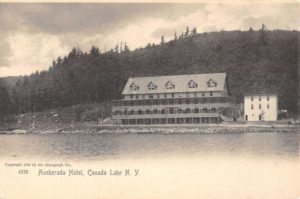

The Auskerada was opened in 1893. It was built on the site of the Canada Lake House which burnt in 1884. The Auskerada became the Allen Inn which burnt on April 23, 1921 [for the Auskerada see McMartin, pp. 70-75].

A second Canada Lake House or Fulton’s Canada Lake Hotel was built in the southeast corner of the Lake. Construction was begun by James Y. Fulton in 1888.  A postcard postmarked 1907 shows a large group of guests on the porch that extended the length of the lakeside of the hotel while there is busy activity along the waterfront. Canoes, rowboats, and a sailboat are visible along with three steamers that would take excursions up the lake. Fulton’s Canada Lake House suffered the same fate as the other grand hotels on the lake burning to the ground on October 12, 1914 [see McMartin, pp. 63-69].

A postcard postmarked 1907 shows a large group of guests on the porch that extended the length of the lakeside of the hotel while there is busy activity along the waterfront. Canoes, rowboats, and a sailboat are visible along with three steamers that would take excursions up the lake. Fulton’s Canada Lake House suffered the same fate as the other grand hotels on the lake burning to the ground on October 12, 1914 [see McMartin, pp. 63-69].

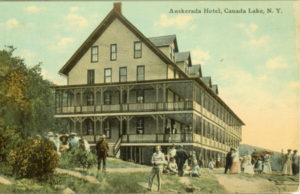

The life in these grand hotels envisioned in these postcards was not “roughing it,” but a world of leisure and polite behavior. As stated in the message on the 1905 Rotograph card of the Canada Lake House : “Where life floats along like a dream.” A postcard from about 1910 of the Auskerada shows an image of upper class ladies and gentlemen promenading on the grounds of the hotel. It echoes the Impressionist paintings of the world of leisure of French society.

The life in these grand hotels envisioned in these postcards was not “roughing it,” but a world of leisure and polite behavior. As stated in the message on the 1905 Rotograph card of the Canada Lake House : “Where life floats along like a dream.” A postcard from about 1910 of the Auskerada shows an image of upper class ladies and gentlemen promenading on the grounds of the hotel. It echoes the Impressionist paintings of the world of leisure of French society.

One of the favorite activities for vacationers was a steamer trip up the Lake for a picnic on West Lake or a trip down the channel to Stewart’s Landing. Paul Bransom describes a steamer trip to Lily Lake in his memoir:

The stage took us to Fulton’s Hotel at the end, the head, of Canada Lake. Mr. Fulton owned a launch which carried passengers down to Stewart’s Landing, about seven miles down the outlet, and back, every fair day.

We boarded the launch with all our gear and traveled the entire length of Canada Lake and on to Lily Lake. As we pass Sand Point, the man running the launch said, “There’s your house, right there.” I looked eagerly but we went on without stopping.

We went right on down to Lily Lake and spent the remaining hours of daylight trying to get ready for night [All Unplanned, pp. 97-98].

Bransom and his wife Grace spent the summer of 1908 at Dr. Granger’s camp which was built in 1905 and is now owned by the Riley family. Next door was the Dwigwam which was built in 1907 by Bransom’s friend, the cartoonist Clare Victor Dwiggins.

Another card printed by the Rotograph Company shows a view of the camps on the north along what is now Kasson Drive. Many being built in the early 1890s, these camps are among the oldest on the lake. The caption erroneously identifies this as a “View from Nick Stoner Island….” The point of view is actually from the south shore.

A series of cards printed by the Rotograph Company, document a steamer trip up the lake. The first shows the steamer Kanaughta from Fulton’s Canada Lake House heading up the Lake with a series of row boats in tow [See McMartin, pp. 78-86]. The Auskerada can be seen in the background.

A later handcolored Rotograph that is postmarked 1907 shows a steamer moving west with the Island in the background. The font used in the caption clearly identifies this as a Rotograph card. The absence of lower border evident in the earlier Rotograph cards indicates a date after 1907 since it was that year that printers were allowed to introduce the “divided back” with the message on the left hand side and the address on the right.

A later handcolored Rotograph that is postmarked 1907 shows a steamer moving west with the Island in the background. The font used in the caption clearly identifies this as a Rotograph card. The absence of lower border evident in the earlier Rotograph cards indicates a date after 1907 since it was that year that printers were allowed to introduce the “divided back” with the message on the left hand side and the address on the right.

A series of slightly later postcards records the progress of a steamer up the Lake. These cards date between 1907 when the “divided back” was introduced and 1911, the postmark of two of the copies of this series . The first shows the steamer shortly after leaving the dock at Fulton’s with the Auskerada in the background.

Another in the series shows a view from the south shore over to the camps along the State Highway now Kasson Drive. A number of today’s camps can be identified. In a message dated September 11, 1911, the sender of this card proudly announces: “On my way to the woods.” Was the choice of the card intended to be a glimpse of the steamer ride to a camping trip into West Lake or down the channel?

Another card numbered 612-44 is based on the 1907 card showing a steamer passing by the island from the north shore.

Another card numbered 612-44 is based on the 1907 card showing a steamer passing by the island from the north shore.

A fourth image in the series shows the island, and the final shows the launch after passing Sand Point and heading west with the north shore and part of Kane Mountain in the background.

The 1905 Rotograph series included other views of the Lake. They can be seen as a sequence moving north along the shore. The series records a walk along today’s Kasson Drive to the Green Lake Bridge. We can begin our walk with a card likely based on a Rotograph original showing London Bridge.

The 1905 Rotograph series included other views of the Lake. They can be seen as a sequence moving north along the shore. The series records a walk along today’s Kasson Drive to the Green Lake Bridge. We can begin our walk with a card likely based on a Rotograph original showing London Bridge.

The next is a card erroneously labeled “Green Lake Bay, Canada Lake, N.Y.,” but is a view from probably the Auskerada dock looking along the shore of what is now Kasson Drive. This handcolored card was clearly a product of the Rotograph Co. The caption’s font and wide lower border, as we have seen, are characteristic of these Rotograph cards. The sentiments of May Scoville, the author of the message at the bottom, are highly debatable: “I don’t think this half as pretty as the Canajoharie falls.”

A Gloversville company, Cowles & Casler, published their versions of the same view. A card with a divided back, indicating a date of 1907 or after, and postmarked 1908, bears the Rotograph, 1905 copyright and title with the Rotograph font, but the reverse identifies the printer as Cowles & Casler of Gloversville. While still printed in Germany, the coloring of this card is much harsher than the Rotograph, 1905 version.

A card postmarked 1909 with a divided back and printed by Cowles & Casler reuses the 1905 Rotograph image. This later card has dropped the Rotograph copyright and uses a different font in the caption at the bottom of the card. The handcoloring has changed the mood of the image. The soft silvery coloration of the Rotograph card has become more saturated and the setting has been changed to twilight.

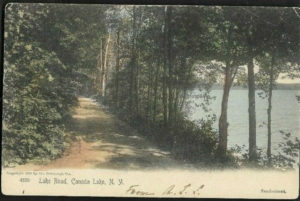

A card entitled “Lake Road, Canada Lake, N.Y.” is another 1905 Rotograph (no. 4330). It shows a view looking south along what is now Kasson Drive from near the Willard Camp near Stony Point. There is a black and white version of this same view:

A card entitled “Lake Road, Canada Lake, N.Y.” is another 1905 Rotograph (no. 4330). It shows a view looking south along what is now Kasson Drive from near the Willard Camp near Stony Point. There is a black and white version of this same view:

We have now reached Stony Point and the view to the Island. Again different versions of this card were produced. The one illustrated above is clearly an original handcolored, 1905 Rotograph.

A later black and white version with a divided back has the same font in the caption as the black and white Lake Road card.

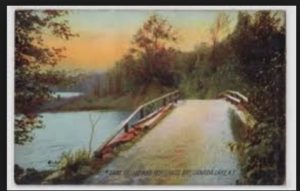

The series culminates at Green Lake Bridge. All the hallmarks of the now familiar handcolored, 1905 Rotograph are evident on the card entitled “Green Lake Bridge and Mettowee Bay, Canada Lake, N.Y.” Like the erroneously identified “Green Lake Bridge” this card has the same soft, silvery coloration.

The series culminates at Green Lake Bridge. All the hallmarks of the now familiar handcolored, 1905 Rotograph are evident on the card entitled “Green Lake Bridge and Mettowee Bay, Canada Lake, N.Y.” Like the erroneously identified “Green Lake Bridge” this card has the same soft, silvery coloration.

A black and white version while based on the original Rotograph is in the same series as the black and white cards of the Lake Road and the view of the Island. All three have the same treatment of the caption.

A black and white version while based on the original Rotograph is in the same series as the black and white cards of the Lake Road and the view of the Island. All three have the same treatment of the caption.

A third version of the Green Lake Bridge card is clearly a sibling to the second Cowles & Casler card entitled “Green Lake Bay” discussed above. Both cards have the same treatment of the caption and the same saturated coloration and twilight setting.

A third version of the Green Lake Bridge card is clearly a sibling to the second Cowles & Casler card entitled “Green Lake Bay” discussed above. Both cards have the same treatment of the caption and the same saturated coloration and twilight setting.

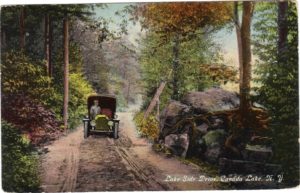

This view of the Green Lake Bridge in 1905 reminds us of the dramatic contrast to our experience of the same bridge today with vehicles of all types racing by.  The challenges facing early automobiles are evident in what might be the earliest postcard depicting an automobile at the Lake. The left hand side driver attempts to negotiate the dirt road rutted by carriage wheels and horses’ hooves. It should be remembered that this “unimproved” road which is now Kasson Drive was the only road heading north from Canada Lake.

The challenges facing early automobiles are evident in what might be the earliest postcard depicting an automobile at the Lake. The left hand side driver attempts to negotiate the dirt road rutted by carriage wheels and horses’ hooves. It should be remembered that this “unimproved” road which is now Kasson Drive was the only road heading north from Canada Lake.

The Rotograph cards, except for the views of the hotels, focus on the rural isolation. The absence of structures is striking in the “Road to Canada Lake,” “Lake Road,” and “Green Lake Bridge” cards. When we look at the “Lake Road” card it is at once familiar and unfamiliar. We easily recognize the view along today’s Kasson Drive, but we also miss the familiar camps, boathouses, and docks of today.

With the loss first of Fulton’s Canada Lake House in 1914 and then the Auskerada in 1921, the era of the grand hotel was over, and the Lake entered a new era that centered around the family summer camp that was made possible by the speed and convenience of the automobile.

Coincidentally with this change in eras from the grand hotel to the family camp, there was a change in the postcard industry. In 1910 tariffs were introduced on German-printed postcards. Companies like Rotograph which depended on the high quality manufacture by German printers could not compete with the higher tariffs and suffered as a consequence. Rotograph would go out of business in 1911. With the tariffs and then the war, German cards became more expensive then impossible to import; production of cards shifted to American companies who wanted to produce larger quantities of cards and could not depend on the higher skilled German printers. To simplify production, white borders were left around the image facilitating the cutting process of the cards. These become known as “White Border Cards,” and were produced from 1913 to the 1930’s.

The next generation of Lake postcards were published largely by C. W. Hughes & Company from Mechanicsville, New York, and are prime examples of “white border cards.”  Active from 1915-1944, the Hughes Co. specialized in scenes from upstate New York, Vermont, and western Massachusetts. The C.W. Hughes & Co. cards were actually printed by the Chicago based Curt Teich Co. The reverse of one of these cards documents this. Along the left border C.W. Hughes & Co. is identified, while along the center border appears “C.T. American Art Colored” which is the Curt Teich Co. (see also). The inclusion of production numbers on most of the Hughes cards printed by Teich allow us to date the cards.

Active from 1915-1944, the Hughes Co. specialized in scenes from upstate New York, Vermont, and western Massachusetts. The C.W. Hughes & Co. cards were actually printed by the Chicago based Curt Teich Co. The reverse of one of these cards documents this. Along the left border C.W. Hughes & Co. is identified, while along the center border appears “C.T. American Art Colored” which is the Curt Teich Co. (see also). The inclusion of production numbers on most of the Hughes cards printed by Teich allow us to date the cards.

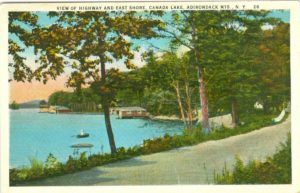

A card entitled “View of Highway and East Shore, Canada Lake” is a typical example of a Hughes-Teich card and when compared to the “Lake Road” card illustrates the change in eras on the Lake. This earlier card shows an unimproved rural lane and as noted above does not include human structures. While as in a good number of Hughes-Teich cards, the “Highway” dominates the foreground with clearly identifiable boat houses, a number which still exist, in the background. The undeveloped shoreline of the older postcard has been replaced by the construction of family houses and boathouses.

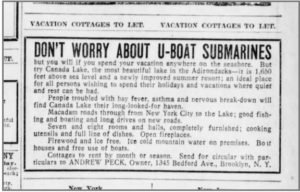

Improvements in the roads played a crucial role in the development of the Lake. Another C.W. Hughes card shows view of the lake with the foreground dominated by a stretch of road with guard rails. Cy Durey who was selling lots for new family camps was instrumental in paving the road along the north shore in 1914 [McMartin, p. 159]. In an ad published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle on July 3, 1917 for summer cottage rentals on Stony Point,

Andrew Peck touts “Macadam roads through from New York City to the Lake; good fishing and boating and long drives on new roads.”

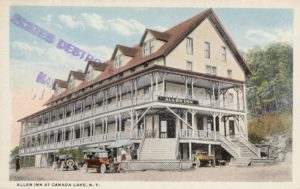

What is probably a Hughes card dating from 1919 shows the Auskerada after it had become the Allen Inn. The inclusion of three automobiles was likely an intentional statement of the changing times.

What is probably a Hughes card dating from 1919 shows the Auskerada after it had become the Allen Inn. The inclusion of three automobiles was likely an intentional statement of the changing times.

The residents along the “State Highway” were lucky with their macadam roads. As new camps were being constructed in the 1920s along the South Shore, the road was extended, but in this case only a dirt road. An excerpt from an August, 1924 letter from George Streeter to his sister Flo Prindle documents the travails facing drivers trying to navigate these dirt roads:

A good share of the excitement this summer apparently is being furnished by difficulties with automobiles. Did you know that I got into trouble back on our road? I don’t think I ever told you but it was one of the real exciting events. It is just such things that keep your spirits fluid. I had been down to Johnstown and had a big load of all sorts of curious things –you certainly remember the table. On returning the road was pretty bad due to the heavy rains but I got through to our side of Dennisons [Alfred Dennison built his camp on the south shore in 1923, now 172 South Shore Road] –when I went up to the hubs in pasty mud, unquestionably stuck and miserable. When they learned of my predicament Julie and the children rose to the occasion and we emptied everything out and lugged them down to the house. You should have seen us filing through the woods carrying bags, boxes, and baskets, looking for all the world like a band of gypsy smugglers – like the second act in Il Travatore. After Julie had fed me up with supper and courage we all returned to the hateful spot. We soon found we could do better things by my prying up the rear hubs with a timber and Julie slipping slabs under the wheels. Then Julie got in and the children and I pushed, and Julie stepped on the gas and she bumped Mr. Ford out of the mire on solid road again. I certainly did love my wife at that moment. Julie you know is what they call a pinch hitter. Don’t you agree with me that events of this sort are what we cherish in our memories.

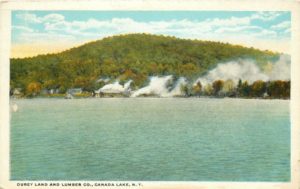

A card dating from 1919 shows the “Durey Land and Lumber Co.” Located at the base of Kane Mountain near today’s Canada Lake Marina, Durey Land and Lumber was incorporated in 1913 [McMartin, p. 156]. The lumber mill was destroyed by fire on the morning of May 20, 1926 [McMartin, p. 172]. Stones from the cribbing of the lumber mill can still be seen offshore.

Request to reader:

As said at the outset, this is just the first stage in the study of Canada Lake Postcards. It is hoped that residents with card collections will be willing to share them. We can learn much more by seeing an individual card in relationship to other cards.

You can contact us at: canadalakesconservation@gmail.com

If you want to send digital copies, please include both sides. It is also useful to have different copies of the same card.

There will be a scanner available over the summer if you are willing to lend your postcards for a short period of time.

Useful resources on the history of postcards:

Smithsonian’s “A Postcard History.”

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Digital Collection (Newberry Library)

The Art History Archive: The History of Postcards